This post is the result of a burning question I had about squalane’s effectiveness as a menstruum. It was clear from my own experimentation that squalane was not as effective as regular fatty oils at capturing certain plant constituents — as evidenced by the color of the infused oil. Try as I might, squalane herbal infusions rarely had anywhere near the vibrance of color I would get from my other infusions using oils like olive oil or tallow. Sometimes they stubbornly remained crystal clear, begging the question(s):

Is the squalane actually extracting anything? Can it be infused with plant constituents for use in skincare formulations or am I wasting my time?

Inquiring minds want to know!

Why use squalane in the first place?

When I asked this question in various herbalism and DIY skincare forums, I almost always got some variation of the same response: Why do you want to infuse squalane anyway? Why not just use a regular carrier oil like olive or almond?

I’m interested in squalane (with an A) because of its strong compatibility to squalene (with an E), a natural component of our skin’s surface lipids. Varying slightly by source, squalene makes up approximately 10-16% of healthy human sebum, along with cholesterol and sterol esters (2-4%), wax esters (20-30%) and triglycerides and fatty acids (50-60%). Squalane (along with jojoba oil and tallow) is an important part of my sebum mimic formula that attempts to approximate the composition of healthy skin lipids.

Squalane is not technically an oil at all. It’s a non-polar, liquid hydrocarbon that doesn’t contain any fatty acids or glycerol, which are the main components of traditional oils. Squalane is often included in skincare products as a lightweight, highly absorbent emollient. It’s colorless, odorless and non-greasy, and is used widely in the cosmetic industry due to its biocompatibility with human skin.

Interestingly, it appears that skincare products containing squalane may also be labeled “oil free.” 🧐

Squalene vs squalane

SqualEne (with an E) is a naturally occurring lipid synthesized by the liver and secreted by the sebaceous glands in humans and other animals. It’s found in particularly large quantities in shark liver oil, which was once the primary source of commercial squalene. Due to ethical and sustainability considerations, most squalene used in cosmetic and personal care products nowadays is going to be derived from plant sources such as olives, wheat germ, amaranth or rice bran.

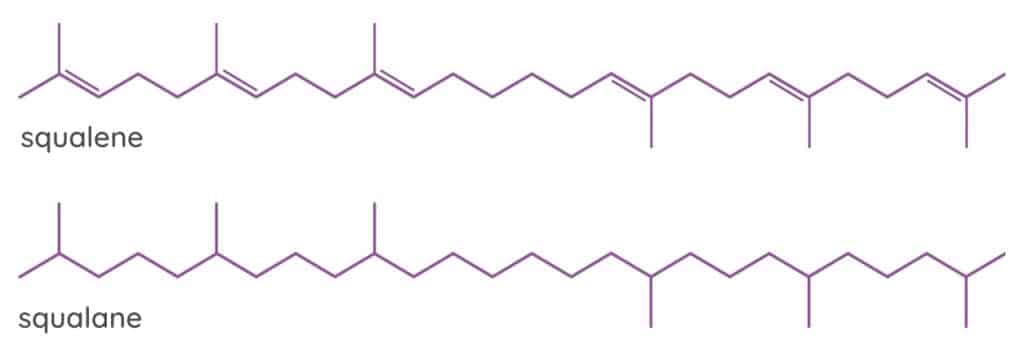

The natural form of SqualEne has six unsaturated double bonds in its chemical structure. Double bonds are more vulnerable to oxidation and degradation because they have more potential reactive sites than single bonds. The double bonds can react with oxygen, heat or light to form free radicals, which damage the skin and cause the oil to become rancid extremely quickly, making it a less than ideal skincare ingredient.

SqualAne (with an A) is a hydrogenated form of squalene in which hydrogen atoms have been added to the double bonds of the unsaturated hydrocarbon molecule, converting them into single bonds. By hydrogenating squalEne to create 100% saturated squalAne, those vulnerable double bonds are eliminated and the resulting oil becomes much more stable and resistant to oxidation.

So if squalEne is a natural part of our skin’s surface lipids, does that mean we’re all walking around with rancid oil on our skin?

Nope!

Our skin’s natural squalene is constantly being replenished, replacing old squalene with new. Our sebum also contains other lipids such as triglycerides, wax esters and cholesterol esters, which can act as stabilizing agents and help to prevent squalene from oxidizing and going rancid. We also produce natural antioxidants such as vitamin E, ubiquinone and glutathione, all of which help to protect against oxidative damage.

But that’s not all!

Unlike hydrogenated squalane, natural squalene has excellent antioxidant capabilities as a free radical scavenger. Squalene uses its susceptibility to oxidation to our advantage, serving as a “sacrificial” antioxidant. When squalene encounters free radicals, it donates electrons to neutralize them, sacrificing itself in the process. In this way, squalene serves an important role as a natural defense against oxidative damage from UV light and other environmental stressors.

So while isolated squalene in a bottle is vulnerable to oxidation and rancidity, the squalene produced by our skin is well-protected and, in turn, helps to protect us!

Ain’t nature grand? ♥

But but but... aren't hydrogenated oils bad for you?

We all know by now that hydrogenated oils can have negative health effects when consumed due to the formation of trans fats, which increase the risk of heart disease and many other health issues. But what about topical hydrogenated oils used on the skin?

While there’s a theoretical possibility that small amounts of hydrogenated oils could be absorbed into the bloodstream through the skin, the available evidence suggests that this is unlikely to occur in significant amounts via topical application.

But isn’t skin our body’s largest organ? Yep it is! But it’s also a barrier designed to protect the body from external harm. It prevents the absorption of larger molecules into the bloodstream, selectively allowing some substances to pass through while preventing others from penetrating too deeply. The molecular size of a substance play a significant role in determining whether it can penetrate the skin barrier and reach the bloodstream.

So when applied topically, most skincare ingredients (including oils) are absorbed into the outermost layers of the skin where they can provide benefits such as moisturizing and improved skin barrier function.

Partially vs fully hydrogenated

Another factor is the difference between partially hydrogenated and fully hydrogenated fats.

Partially hydrogenated oils are created by adding hydrogen to liquid oils, which creates solid form that is more stable and has a longer shelf life. As the name suggests, the partial hydrogenation process is stopped before all of the double bonds in the oil are completely saturated with hydrogen, resulting in a partially hydrogenated oil that contains both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Some of these remaining double bonds may be converted into trans double bonds, where the carbon chains end up on opposite sides of the double bond instead of the same side, resulting in an artificial trans fat.

Fully hydrogenated oils, on the other hand, are created by fully saturating the oil with hydrogen, which results in a 100% saturated oil that contains no trans fats. Full hydrogenation converts all of the double bonds to single bonds, resulting in a fully saturated fatty acid. Since there are no remaining double bonds, there is no opportunity for any trans configurations to form.

Squalane is an example of a fully hydrogenated oil. Unlike most hydrogenated oils, though, squalane is not solid at room temperature because of its unusually low melting point (23.36°F).

TLDR: While I wouldn’t recommend consuming either type of artificially hydrogenated oil, my read of the available info is that squalane in topical applications is probably fine.

Infusing squalane

Squalane is a single, fully saturated hydrocarbon with the formula C₃₀H₆₂. It’s non-polar, low-viscosity and has a relatively low molecular weight compared to the more complex lipids found in traditional fatty oils. Because of its simple structure, squalane has some limitations as a solvent — particularly when it comes to extracting larger, more complex plant constituents that are more readily solubilized by the diverse lipid profile of carrier oils like olive, coconut or tallow.

Fatty oils contain a complex mix of triglycerides, phospholipids, free fatty acids and minor unsaponifiables, which gives them a broader solubility range and enhances their ability to extract oil-soluble plant constituents.

Phytosterols (like beta-sitosterol in comfrey or stigmasterol in red clover) and carotenoids (like beta-carotene) are higher molecular weight compounds that tend to solubilize more effectively in these complex lipid environments. The same goes for many plant resins, such as those found in benzoin.

For example: Here’s a photo of a benzoin infusion I attempted using squalane. I used gentle heat (around 100F) in my cabinet dehydrator over a period of 3 days. As you can see, some of the resin extracted into the squalane — but much of it remained undissolved, separating out and either floating or settling at the bottom of the jar. Not a total failure, but not quite the benzoin-infused squalane I was hoping for either.

Hypericin, the red pigment found in St. John’s wort, adds another wrinkle. It’s a semi-polar molecule and not truly oil soluble like beta-carotene. It tends to extract better in alcohol or alcohol/oil combinations — particularly when paired with gentle heat or an alcohol intermediary method. Squalane alone is unlikely to pull much hypericin.

That said, squalane may still be useful for extracting less complex, lower molecular weight constituents such as certain flavonoids and terpenes. Its effectiveness as a solvent ultimately depends on the specific plant constituents you’re hoping to harness. If you’re not already using it, Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases is an invaluable resource for understanding what compounds a particular plant contains.

A word of caution: don’t just pour squalane over your herb and hope for the best — that’s a recipe for disappointment. It’s a more finicky solvent and often needs a little help.

One way to boost squalane’s solvent power is to use an alcohol intermediary extraction, moistening your herb with a small amount of high-proof ethanol prior to infusing in squalane. This step helps break down cell walls and dissolves certain alcohol-soluble constituents that squalane alone may not extract well.

Gentle heat also goes a long way. Applying consistent, low heat during infusion helps soften cell walls and improves the solubility of many plant compounds without harming the oil or degrading delicate phytochemicals.

Generally speaking, any plant containing oil-soluble constituents can be infused in squalane — but you’ll want to be intentional about which compounds you’re targeting and choose your method accordingly.

Have you experimented with infused squalane before? Tell us about it in the comments! ♥

5 Responses

Loved this post. I recently strained two sugarcane Squalane infusions – one with organic coffee grounds , and the other with lavender and vanilla bean.

Both came out very fragrant. The coffee infusion is yellowish brown in color, and the Squalane went from clear to yellow with the lavender and vanilla infusion. I much prefer the scent of lavender when it is cold extracted vs. in its essential oil form.

I used these both in some nice creamy tallow moisturizers!

I really appreciate this experiment you’ve done with squalane! There’s little to no information on infusing herbs into this oil but I’m trying to formulate an eczema oil. Thanks for your post and research ☺️

Thank you, Lauren! I’m so happy it was helpful! ♥

Thank you for sharing this! I am currently infusing sugarcane squalane with lemon balm…my first go at it and was hoping I wasn’t botching it. So far the solution is a lovely mild yellow. I placed it in a west facing window so it warmed a bit and I was wondering how concerned I should be about stability. Can this be added to my tallow formula without additional stabilization, being that squalane isn’t technically an oil?

Hi Amy, Your lemon balm-infused squalane sounds lovely! That mild yellow hue is a great sign you’re pulling out some of the lighter-weight, oil-soluble constituents like flavonoids, terpenes and possibly a touch of carotenoids. Those are exactly the kinds of compounds squalane is well-suited to extract!

Squalane is highly resistant to oxidation and rancidity, so placing it in a warm window won’t harm the squalane itself. That said, extended exposure to sunlight can degrade some of lemon balm’s more delicate compounds — particularly its volatile oils like citral and linalool. You might consider using an amber jar or covering your jar with a paper bag or dish towel to help protect those more fragile constituents.

Yes, you can absolutely incorporate your lemon balm-infused squalane into your tallow-based formulas without the need for additional antioxidants or preservatives — assuming your final product doesn’t include any water-based ingredients like aloe or hydrosols. Tallow, if well-rendered and free of moisture, is also quite shelf stable, and the combination should make for a beautifully nourishing product with excellent longevity ♥